Clever the Twain Shall Meet

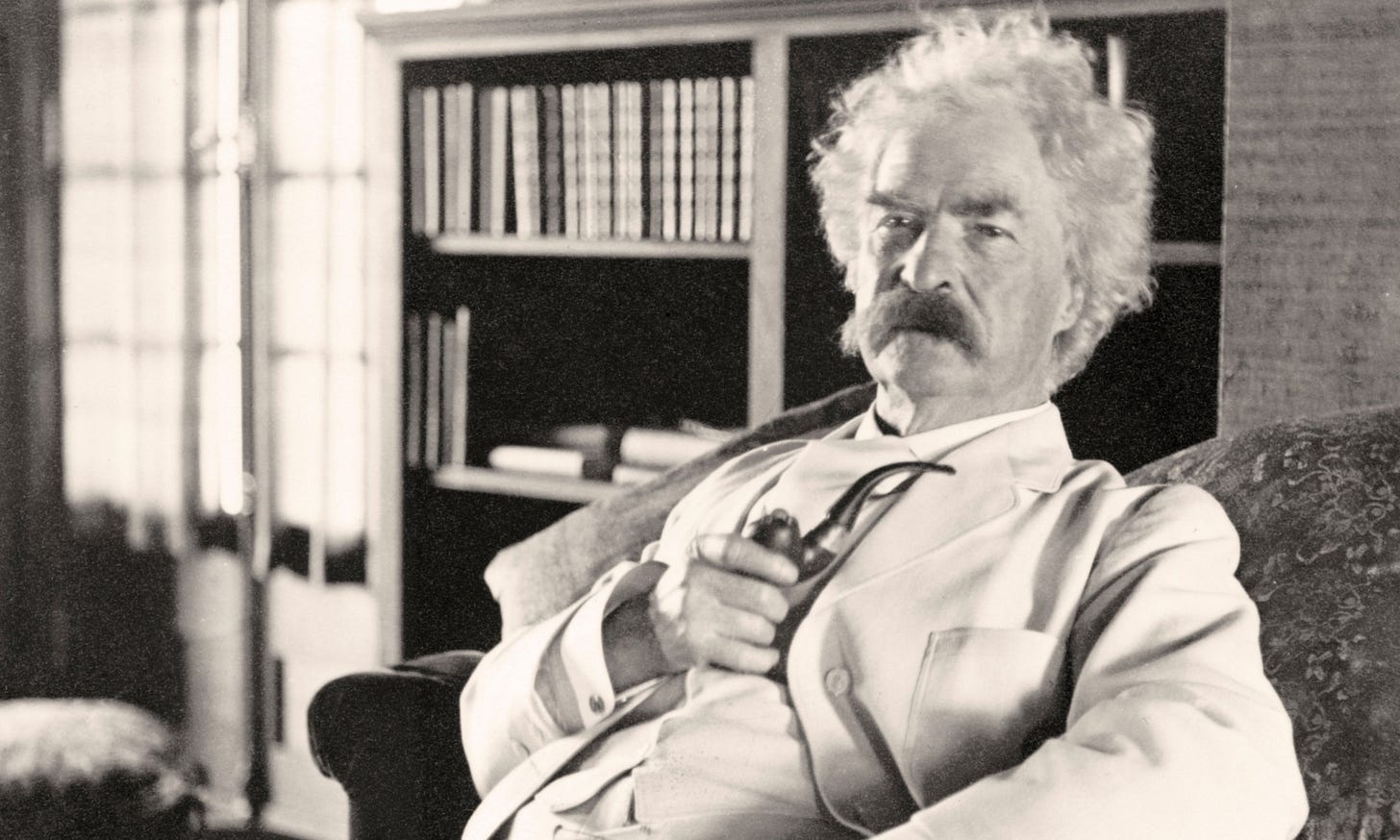

An epic new biography of Samuel Clemens confirms the Missourian’s literary mastery but contends that the most important character he ever created was his own.

by Sara Bhatia

In March, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts bestowed its annual Mark Twain Prize for American Humor on the former late-night talk show host Conan O’Brien. At the awards ceremony, there was a frisson of tension in the audience. Just one month earlier, President Donald Trump had attacked the center’s programming as too “woke,” dismissed its leadership, and installed himself as chairman of the board, sparking widespread protest in the arts community.

On the Kennedy Center’s stage, many of the comedians roasting O’Brien also took aim at the president. But O’Brien, who has built his reputation as a nonpartisan observer, seemingly kept his powder dry. Instead, he spoke of the legacy of Mark Twain and the profound honor of receiving the award.

“Don’t be distracted by the white suit and the cigar and the riverboat,” O’Brien chided. “Twain is alive, vibrant, and vitally relevant today.” He spoke of Twain’s hatred of bullies, his support for underdogs ranging from the formerly enslaved to Chinese immigrants—“he punched up, not down”—along with his hatred of intolerance, racism, and anti-Semitism, and his suspicion of populism and jingoism. Though O’Brien never mentioned Trump, the audience slowly awakened to the comedian’s subversive subtext. He concluded to sustained applause, “Twain wrote, ‘Patriotism is supporting your country all of the time, and your government when it deserves it.’”

And thus with just a few spare sentences, Conan O’Brien made Mark Twain—the mustachioed, wisecracking author of America’s Gilded Age—once again relevant to American politics.

***

So closely did O’Brien echo the praise of the writer’s “core principles” and irreverent wit that I wondered if someone had slipped him the advance galleys of Ron Chernow’s sparkling new biography. In Mark Twain, the acclaimed biographer takes a sledgehammer to the mythology of the quintessential American author. Like O’Brien, Chernow challenges the “sanitized view of a humorous man in a white suit, dispensing witticisms with a twinkling eye,” to demonstrate that Twain was among our nation’s most trenchant and biting social critics. Chernow asserts that “far from being a soft-shoe, cracker-barrel philosopher, he was a waspish man of decided opinions delivering hard and uncomfortable truths. His wit was laced with vinegar, not oil.”

In his personal life, too, Twain belied his deliberately crafted, jovial public persona. Chernow wryly notes, “Mark Twain could serve as both a social critic of something and an exemplar of the very thing he criticized.” Indeed, the author who charmed audiences with his folksy demeanor and sought to create “a new democratic literature for ordinary people” while skewering elites and their institutions was exceptionally well read and cosmopolitan. He had lived for more than a decade in Europe, residing in grand châteaus and villas, and traveled the world, crossing the Atlantic 29 times. Twain’s barefoot boyhood on the banks of the Mississippi River was the stuff of legend, but the author spent most of his adulthood in New England, in a 25-room mansion with a fleet of servants, purchased with cash from his wealthy wife.

Chernow, the Pulitzer Prize– and National Book Award–winning writer of popular biographies of Ulysses S. Grant, George Washington, and Alexander Hamilton, tackles his complicated, often contradictory subject with nuance and prolific research. Chernow explores the author’s enormous oeuvre—a gratifying surprise for those whose familiarity with Twain resides in hazy middle school memories of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

But this is no literary critique. Chernow asserts that Twain was “the most original character in American history,” and he is fascinated by him more as a man than as an author, reveling in his theatricality, both on the stage and off. He writes,

Mark Twain discarded the image of the writer as a contemplative being, living a cloistered existence, and thrust himself into the hurly-burly of American culture, capturing the wild, uproarious energy throbbing in the heartland. Probably no other American author has led such an eventful life.

Mark Twain is a massive brick of a book, comprising more than a thousand pages, and it is the mining of Twain’s private life and its intertwining with his public image that lends the book its physical heft and its most surprising and compelling content. Chernow concludes that “Mark Twain’s foremost creation—his richest and most complex gift to posterity—may well have been his own inimitable personality, the largest literary personality that America has produced.”

***

Twain was easily the most famous writer in Gilded Age America, an era whose name was coined by Twain himself. He was the nation’s first celebrity author, a consummate storyteller, the nation’s most quoted person, and for many outside the U.S., the archetypal American. He mastered a vast array of literary formats, including travelogues, novels, essays, political tracts, plays, and historical romances. He created a uniquely American voice that captured the vernacular speech of the young nation. As famous an orator as a writer, Twain elevated storytelling into a wholly original theatrical genre, conducting speaking tours that attracted massive crowds and took him around the world, from Hawaii to Australia.

Despite his myriad achievements, Twain felt unappreciated by the literary establishment, and chafed at the label “humorist,” fearing that audiences saw him as little more than vaudevillian. In 1907, Oxford University presented him with an honorary degree. For a man of humble origins who had left school at 12, Twain considered the diploma the pinnacle of his career, and he proudly donned the resplendent scarlet graduation gown to wear at formal events for the remainder of his life—including, charmingly, his daughter’s wedding.

Click here to continue reading online.

Sara Bhatia is an independent museum consultant who writes about museums, history, and culture.

NEW Episode of the Washington Monthly Podcast!

Ep. 21: Trump's First 100 Days: FDR in Reverse w/ Jonathan Alter

In his first inaugural address, FDR famously told the nation that there was "nothing to fear but fear itself." Fast forward to 2025, and fear is the hallmark of Donald Trump's first 100 days in office. Contributing Editor Jonathan Alter, who wrote the definitive book on FDR's use of executive power in his first 100 days, contrasts the enduring legacy of Roosevelt to the chaos of Trump.

You can subscribe on iTunes, Spotify, and YouTube.

PLUS: Today, the Supreme Court will hear arguments about Trump's claim to be able to unilaterally change the meaning of birthright citizenship in the 14th Amendment.

Legal Affairs Editor Garrett Epps explains that the Court must uphold birthright citizenship, not because the Constitution says so, but because of Congress. Under the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, Congress explicitly granted citizenship to all babies born on US soil. Watch Garrett's explainer here!

Find the Washington Monthly on Social

We're on BlueSky @washingtonmonthly.com

We're on Twitter @monthly

We're on YouTube @washingtonmonthly9554

We're on Threads @WAMonthly

We're on Instagram @WAMonthly

We're on Facebook @WashingtonMonthly

Don't think there is any recent biography of Twain/Clemens that doesn't point out his role as a social critic — a very harsh critic of his country.